How Fossil Fuel Money Made Climate Change Denial the Word of God

Marc Rubio said “I believe in freedom of speech and I believe spending money on political campaigns is a form of political speech that is protected under the Constitution,” . “And the people who seem to have a problem with it are the ones who only want Unions to be able to do it, their friends in Hollywood to be able to do it and their friends in the media to be able to do it.” Ted Cruz chimed in, calling Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid’s repeated attacks on the Koch brothers in the 2012 and 2014 cycles, “grotesque and offensive.” This PANEL constituted three major 2016 candidates openly jockeying for the blessing of the Koch network. Ryan noted—a clear subversion of the Citizens United ruling whose rationale for allowing outside groups to spend unlimited sums was that they would not be able to directly coordinate with candidates or their committees. But that doesn’t mean it hasn’t happened before. Last April, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, Ohio Gov. John Kasich and former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush flew to Las Vegas for an audition of sorts with billionaire Sheldon Adelson, who famously kept Newt Gingrich’s 2012 presidential campaign afloat, even after the former Speaker’s electoral prospects all but vanished. So unabashed were the prospective candidates’ pandering to the casino mogul that The Atlantic’s Molly Ball dubbed the event the “Sheldon Adelson Suck-Up Fest.” “The laws are a joke when presidential candidates can be bought by a dark money group like the Kochs.” Presidential super PACs are more necessity than novelty in a modern campaign. Four 2016 candidates have formed POLITICAL NONPROFITS, which have even looser rules around disclosure. (four Republicans—Rick Perry, Rick Santorum, Bobby Jindal, and John Kasich Such activities were once the province of campaign committees, where donors are named and expenses are tallied. But by raising money through "social welfare" nonprofits, these not-yet-candidates are avoiding disclosure of both their financiers and what, exactly, they are financing.) Hillary Clinton's Super PAC raised $11 million in 2014. There was a time when an $11 million would have been a big kitty, but next to this, it barely purrs. the

Koch Brothers' Toxic Empire

ENERGY SOLUTIONS

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Together, Charles and David

Koch control one of the world's largest fortunes,

|

|

|

|

| Physical Pollution

Dirty Business Practices

Dirty Politics

HISTORY

Environmental Disasters

Derivatives Trading with Iran Tar Sands Unfettered by financial regulation Risky Trading KOCH Companies Republican Party -- a protection racket for Koch |

|

||

What is less clear is where all that money comes from. Koch Industries is headquartered in a squat, smoked-glass building that rises above the prairie on the outskirts of Wichita, Kansas. The building, like the brothers' fiercely private firm, is literally and figuratively a black box. Koch touts only one top-line financial figure: $115 billion in annual revenue, as estimated by Forbes. By that metric, it is larger than IBM, Honda or Hewlett-Packard and is America's second-largest private company after agribusiness colossus Cargill. The company's stock response to inquiries from reporters: "We are privately held and don't disclose this information."

But Koch Industries is not entirely opaque. The company's troubled legal history – including a trail of congressional investigations, Department of Justice consent decrees, civil lawsuits and felony convictions – augmented by internal company documents, leaked State Department cables, Freedom of Information disclosures and company whistle-blowers, combine to cast an unwelcome spotlight on the toxic empire whose profits finance the modern GOP.

Under the nearly five-decade reign of CEO Charles Koch, the company has paid out record civil and criminal environmental penalties. And in 1999, a jury handed down to Koch's pipeline company what was then the largest wrongful-death judgment of its type in U.S. history, resulting from the explosion of a defective pipeline that incinerated a pair of Texas teenagers.

The volume of Koch Industries' toxic output is staggering. According to the

University of Massachusetts Amherst's Political Economy

Research Institute, only three companies rank among

the top 30 polluters of America's air, water and climate:

ExxonMobil, American Electric Power and Koch Industries.

Thanks in part to its 2005 purchase of paper-mill giant

Georgia-Pacific, Koch Industries dumps more pollutants into the nation's

waterways than General Electric and International Paper combined.

The company ranks 13th in the nation for toxic air pollution. Koch's climate

pollution, meanwhile, outpaces oil giants including Valero, Chevron and Shell.

Across its businesses, Koch generates 24 million metric tons of

greenhouse gases a year.

For Koch, this license to pollute amounts to a perverse, hidden subsidy. The cost is borne by communities in cities like Port Arthur, Texas, where a Koch-owned facility produces as much as 2 billion pounds of petrochemicals every year. In March, Koch signed a consent decree with the Department of Justice requiring it to spend more than $40 million to bring this plant into compliance with the Clean Air Act.

| The toxic history of Koch Industries is not

limited to physical pollution. It also extends to the company's business

practices, which have been the target of numerous federal investigations,

resulting in several indictments and convictions, as well as a whole host of

fines and penalties. And in one of the great ironies of the Obama years, the president's financial-regulatory reform seems to benefit Koch Industries. The company is expanding its high-flying trading empire precisely as Wall Street banks – facing tough new restrictions, which Koch has largely escaped – are backing away from commodities speculation. It is often said that the Koch brothers are in the oil business. That's true as far as it goes – but Koch Industries is not a major oil producer. Instead, the company has woven itself into every nook of the vast industrial web that transforms raw fossil fuels into usable goods. Koch-owned businesses trade, transport, refine and process fossil fuels, moving them across the world and up the value chain until they become things we forgot began with hydrocarbons: fertilizers, Lycra, the innards of our smartphones. The company controls at least four oil refineries, six ethanol plants, a natural-gas-fired power plant and 4,000 miles of pipeline. Until recently, Koch refined roughly five percent of the oil burned in America (that percentage is down after it shuttered its 85,000-barrel-per-day refinery in North Pole, Alaska, owing, in part, to the discovery that a toxic solvent had leaked from the facility, fouling the town's groundwater). From the fossil fuels it refines, Koch also produces billions of pounds of petrochemicals, which, in turn, become the feedstock for other Koch businesses. In a journey across Koch Industries, what enters as a barrel of West Texas Intermediate can exit as a Stainmaster carpet. |

A 1996 explosion of a Koch-owned pipeline in Texas killed two teens.

(Photo: National Transportation Safety Board)

|

|||||||||

| Koch's hunger for growth is insatiable: Since

1960, the company brags, the value of Koch Industries has grown 4,200-fold,

outpacing the Standard & Poor's index by nearly 30 times. On average, Koch

projects to double its revenue every six years. Koch is now a key player in

the fracking boom that's vaulting the

United States past Saudi Arabia as the world's top oil producer, even as

it's endangering America's groundwater. In 2012, a Koch subsidiary opened a

pipeline capable of carrying 250,000 barrels a

day of fracked crude from South Texas to

Corpus Christi, where the company owns a

refinery complex, and it has announced plans to further expand its Texas

pipeline operations. In a recent acquisition, Koch bought

Frac-Chem, a top provider of hydraulic

fracturing chemicals to drillers. Thanks to the Bush

administration's anti-regulatory agenda – which Koch Industries helped

craft – Frac-Chem's chemical cocktails,

injected deep under the nation's aquifers, are almost entirely

exempt from the Safe

Drinking Water Act. Koch is also long on the richest – but also the dirtiest and most carbon-polluting – oil deposits in North America: the tar sands of Alberta. The company's Pine Bend refinery, near St. Paul, Minnesota, processes nearly a quarter of the Canadian bitumen exported to the United States – which, in turn, has created for Koch Industries a lucrative sideline in petcoke exports. Denser, dirtier and cheaper than coal, petcoke is the dregs of tar-sands refining. U.S. coal plants are largely forbidden from burning petcoke, but it can be profitably shipped to countries with lax pollution laws like Mexico and China. One of the firm's subsidiaries, Koch Carbon, is expanding its Chicago terminal operations to receive up to 11 million tons of petcoke for global export. In June, the EPA noted the facility had violated the Clean Air Act with petcoke particulates that endanger the health of South Side residents. "We dispute that the two elevated readings" behind the EPA notice of violation "are violations of anything," Koch's top lawyer, Mark Holden, told Rolling Stone, insisting that Koch Carbon is a good neighbor. Over the past dozen years, the company has quietly acquired leases for 1.1 million acres of Alberta oil fields, an area larger than Rhode Island. By some estimates, Koch's direct holdings nearly double ExxonMobil's and nearly triple Shell's. In May, Koch Oil Sands Operating LLC of Calgary, Alberta, sought permits to embark on a multi-billiondollar tar-sands-extraction operation. This one site is projected to produce 22 million barrels a year – more than a full day's supply of U.S. oil. Charles Koch, the 78-year-old CEO and chairman of the board of Koch Industries, is inarguably a business savant. He presents himself as a man of moral clarity and high integrity. "The role of business is to produce products and services in a way that makes people's lives better," he said recently. "It cannot do so if it is injuring people and harming the environment in the process." HISTORYAlmost from the beginning, Koch Industries' risk-taking crossed over into recklessness. The OPEC oil embargo hit the company hard. Koch had made a deal giving the company the right to buy a large share of Qatar's export crude. At the time, Koch owned five supertankers and had chartered many others. When the embargo hit, Koch had upward of half a billion dollars in exposure to tankers and couldn't deliver OPEC oil to the U.S. market, creating what Charles has called "large losses." Soon, Koch Industries was caught overcharging American customers. The Ford administration in the summer of 1974 compelled Koch to pay out more than $20 million in rebates and future price reductions. Koch Industries' manipulations were about to get more audacious. In the late 1970s, the federal government parceled out exploration tracts, using a lottery in which anyone could score a 10-year lease at just $1 an acre – a game of chance that gave wildcat prospectors the same shot as the biggest players. Koch didn't like these odds, so it enlisted scores of frontmen to bid on its behalf. In the event they won the lottery, they would turn over their leases to the company. In 1980, Koch Industries pleaded guilty to five felonies in federal court, including conspiracy to commit fraud. With Republicans and Democrats united in regulating the oil business, Charles had begun throwing his wealth behind the upstart Libertarian Party, seeking to transform it into a viable third party. Over the years, he would spend millions propping up a league of affiliated think tanks and front groups – a network of Libertarians that became known as the "Kochtopus." Charles even convinced David to stand as the Libertarian Party's vice-presidential candidate in 1980 – a clever maneuver that allowed David to lavish unlimited money on his own ticket. The Koch-funded 1980 platform was nakedly in the brothers' self-interest – slashing federal regulatory agencies, offering a 50 percent tax break to top earners, ending the "cruel and unfair" estate tax and abolishing a $16 billion "windfall profits" tax on the oil industry. The words of Libertarian presidential candidate Ed Clark's convention speech in Los Angeles ring across the decades: "We're sick of taxes," he declared. "We're ready to have a very big tea party." In a very real sense, the modern Republican Party was on the ballot that year – and it was running against Ronald Reagan. Charles' management style and infatuation with far-right politics were endangering his grip on the company. Bill believed his brothers' political spending was bad for business. "Pretty soon, we would get the reputation that the company and the Kochs were crazy," he said. In late 1980, with Frederick's backing, Bill launched an unsuccessful battle for control of Koch Industries, aiming to take the company public. Three years later, Charles and David bought out their brothers for $1.1 billion. But the speed with which Koch Industries paid off the buyout debt left Bill convinced, but never quite able to prove, he'd been defrauded. He would spend the next 18 years suing his brothers, calling them "the biggest crooks in the oil industry." Bill also shared these concerns with the federal government. Thanks in part to his efforts, in 1989 a Senate committee investigating Koch business with Native Americans would describe Koch Oil tactics as "grand larceny." In the late 1980s, Koch was the largest purchaser of oil from American tribes. Senate investigators suspected the company was making off with more crude from tribal oil fields than it measured and paid for. They set up a sting, sending an FBI agent to coordinate stakeouts of eight remote leases. Six of them were Koch operations, and the agents reported "oil theft" at all of them. One of Koch's gaugers would refer to this as "volume enhancement." But in sworn testimony before a Texas jury, Phillip Dubose, a former Koch pipeline manager, offered a more succinct definition: "stealing." The Senate committee concluded that over the course of three years Koch "pilfered" $31 million in Native oil; in 1988, the value of that stolen oil accounted for nearly a quarter of the company's crude-oil profits. "I don't know how the company could have figures like that," the FBI agent testified, "and not have top management know that theft was going on." In his own testimony, Charles offered that taking oil readings "is a very uncertain art" and that his employees "aren't rocket scientists." Koch's top lawyer would later paint the company as a victim of Senate "McCarthyism." Dirty PoliticsBy this time, the Kochs had soured on the Libertarian Party, concluding that control of a small party would never give them the muscle they sought in the nation's capital. Now they would spend millions in efforts to influence – and ultimately take over – the GOP. The work began close to home; the Kochs had become dedicated patrons of Sen. Bob Dole of Kansas, who ran interference for Koch Industries in Washington. On the Senate floor in March 1990, Dole gloatingly cautioned against a "rush to judgment" against Koch, citing "very real concerns about some of the evidence on which the special committee was basing its findings." A grand jury investigated the claims but disbanded in 1992, without issuing indictments. Arizona Sen. Dennis DeConcini was "surprised and disappointed" at the decision to drop the case. "Our investigation was some of the finest work the Senate has ever done," he said. "There was an overwhelming case against Koch." But Koch did not avoid all punishment. Under the False Claims Act, which allows private citizens to file lawsuits on behalf of the government, Bill sued the company, accusing it of defrauding the feds of royalty income on its "volumeenhanced" purchases of Native oil. A jury concluded Koch had submitted more than 24,000 false claims, exposing Koch to some $214 million in penalties. Koch later settled, paying $25 million. Selfinterest continued to define Koch Industries' adventures in public policy. In the early 1990s, in a high-profile initiative of the first-term Clinton White House, the administration was pushing for a levy on the heat content of fuels. Known as the BTU tax, it was the earliest attempt by the federal government to recoup damages from climate polluters. But Koch Industries could not stand losing its most valuable subsidy: the public policy that allowed it to treat the atmosphere as an open sewer. Richard Fink, head of Koch Company's Public Sector and the longtime mastermind of the Koch brothers' political empire, confessed to The Wichita Eagle in 1994 that Koch could not compete if it actually had to pay for the damage it did to the environment: "Our belief is that the tax, over time, may have destroyed our business." To fight this threat, the Kochs funded a "grassroots" uprising – one that foreshadowed the emergence, decades later, of the Tea Party. The effort was run through Citizens for a Sound Economy, to which the brothers had spent a decade giving nearly $8 million to create what David Koch called "a sales force" to communicate the brothers' political agenda through town hall meetings and anti-tax rallies designed to look like spontaneous demonstrations. In 1994, David Koch bragged that CSE's campaign "played a key role in defeating the administration's plans for a huge and cumbersome BTU tax." Environmental DisastersDespite the company's increasingly sophisticated political and public-relations operations, Charles' philosophy of regulatory resistance was about to bite Koch Industries – in the form of record civil and criminal financial penalties imposed by the Environmental Protection Agency. Koch entered the 1990s on a pipeline-buying spree. By 1994, its network measured 37,000 miles. According to sworn testimony from former Koch employees, the company operated its pipelines with almost complete disregard for maintenance. As Koch employees understood it, this was in keeping with their CEO's trademarked business philosophy, MarketBased Management (MBM). For Charles, MBM – first communicated to employees in 1991 – was an attempt to distill the business practices that had grown Koch into one of the largest oil businesses in the world. To incentivize workers, Koch gives employees bonuses that correlate to the value they create for the company. "Salary is viewed only as an advance on compensation for value," Koch wrote, "and compensation has an unlimited upside." To prevent the stagnation that can often bog down big enterprises, Koch was also determined to incentivize risk-taking. Under MBM, Koch Industries books opportunity costs – "profits foregone from a missed opportunity" – as though they were actual losses on the balance sheet. Koch employees who play it safe, in other words, can't strike it rich. On paper, MBM sounds innovative and exciting. But in Koch's hyperaggressive corporate culture, it contributed to a series of environmental disasters. Applying MBM to pipeline maintenance, Koch employees calculated that the opportunity cost of shutting down equipment to ensure its safety was greater than the profit potential of pushing aging pipe to its limits. The fact that preventive pipeline maintenance is required by law didn't always seem to register. Dubose, a 26-year Koch veteran who oversaw pipeline areas in Louisiana, would testify about the company's lax attitude toward maintenance. "It was a question of money. It would take away from our profit margin." The testimony of another pipeline manager would echo that of Dubose: "Basically, the philosophy was 'If it ain't broke, don't work on it.'" When small spills occurred, Dubose testified, the company would cover them up. He recalled incidents in which the company would use the churn of a tugboat's engine to break up waterborne spills and "just kind of wash that thing on down, down the river." On land, Dubose said, "They might pump it [the leaked oil] off into a drum, then take a shovel and just turn the earth over." When larger spills were reported to authorities, the volume of the discharges was habitually low-balled, according to Dubose. Managers pressured employees to falsify pipeline-maintenance records filed with federal authorities; in a sworn affidavit, pipeline worker Bobby Conner recalled arguments with his manager over Conner's refusal to file false reports: "He would always respond with anger," Conner said, "and tell me that I did not know how to be a Koch employee." Conner was fired and later settled a wrongful-termination suit with Koch Gateway Pipeline. Dubose testified that Charles was not in the dark about the company's operations. "He was in complete control," Dubose said. "He was the one that was line-driving this Market-Based Management at meetings." Before the worst spill from this time, Koch employees had raised concerns about the integrity of a 1940s-era pipeline in South Texas. But the company not only kept the line in service, it increased the pressure to move more volume. When a valve snapped shut in 1994, the brittle pipeline exploded. More than 90,000 gallons of crude spewed into Gum Hollow Creek, fouling surrounding marshlands and both Nueces and Corpus Christi bays with a 12-mile oil slick. By 1995, the EPA had seen enough. It sued Koch for gross violations of the Clean Water Act. From 1988 through 1996, the company's pipelines spilled 11.6 million gallons of crude and petroleum products. Internal Koch records showed that its pipelines were in such poor condition that it would require $98 million in repairs to bring them up to industry standard. Ultimately, state and federal agencies forced Koch to pay a $30 million civil penalty – then the largest in the history of U.S. environmental law – for 312 spills across six states. Carol Browner, the former EPA administrator, said of Koch, "They simply did not believe the law applied to them." This was not just partisan rancor. Texas Attorney General John Cornyn, the future Republican senator, had joined the EPA in bringing suit against Koch. "This settlement and penalty warn polluters that they cannot treat oil spills simply as the cost of doing business," Cornyn said. (The Kochs seem to have no hard feelings toward their one-time tormentor; a lobbyist for Koch was the number-two bundler for Cornyn's primary campaign this year.) Koch wasn't just cutting corners on its pipelines. It was also violating federal environmental law in other corners of the empire. Through much of the 1990s at its Pine Bend refinery in Minnesota, Koch spilled up to 600,000 gallons of jet fuel into wetlands near the Mississippi River. Indeed, the company was treating the Mississippi as a sewer, illegally dumping ammonia-laced wastewater into the river – even increasing its discharges on weekends when it knew it wasn't being monitored. Koch Petroleum Group eventually pleaded guilty to "negligent discharge of a harmful quantity of oil" and "negligent violation of the Clean Water Act," was ordered to pay a $6 million fine and $2 million in remediation costs, and received three years' probation. This facility had already been declared a Superfund site in 1984. In 2000, Koch was hit with a 97-count indictment over claims it violated the Clean Air Act by venting massive quantities of benzene at a refinery in Corpus Christi – and then attempted to cover it up. According to the indictment, Koch filed documents with Texas regulators indicating releases of just 0.61 metric tons of benzene for 1995 – one-tenth of what was allowed under the law. But the government alleged that Koch had been informed its true emissions that year measured 91 metric tons, or 15 times the legal limit. By the time the case came to trial, however, George W. Bush was in office and the indictment had been significantly pared down – Koch faced charges on only seven counts. The Justice Department settled in what many perceived to be a sweetheart deal, and Koch pleaded guilty to a single felony count for covering up the fact that it had disconnected a key pollution-control device and did not measure the resulting benzene emissions – receiving five years' probation. Despite skirting stiffer criminal prosecution, Koch was handed $20 million in fines and reparations – another historic judgment. DerivativesBut even as compliance began to improve among its industrial operations, the company aggressively expanded its trading activities into the Wild West frontier of risky financial instruments. In 2000, the Commodity Futures Modernization Act had exempted many of these products from regulation, and Koch Industries was among the key players shaping that law. Koch joined up with Enron, BP, Mobil and J. Aron – a division of Goldman Sachs then run by Lloyd Blankfein – in a collaboration called the Energy Group. This corporate alliance fought to prohibit the federal government from policing oil and gas derivatives. "The importance of derivatives for the Energy Group companies . . . cannot be overestimated," the group's lawyer wrote to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in 1998. "The success of this business can be completely undermined by . . . a costly regulatory regime that has no place in the energy industry." Koch had long specialized in "over-the-counter" or OTC trades – private, unregulated contracts not disclosed on any centralized exchange. In its own letter to the CFTC, Koch identified itself as "a major participant in the OTC derivatives market," adding that the company not only offered "risk-management tools for its customers" but also traded "for its own account." Making the case for what would be known as the Enron Loophole, Koch argued that any big firm's desire to "maintain a good reputation" would prevent "widespread abuses in the OTC derivatives market," a darkly hilarious claim, given what would become not only of Enron, but also Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers and AIG. The Enron Loophole became law in December 2000 – pushed along by Texas Sen. Phil Gramm, giving the Energy Group exactly what it wanted. "It completely exempted energy futures from regulation," says Michael Greenberger, a former director of trading and markets at the CFTC. "It wasn't a matter of regulators not enforcing manipulation or excessive speculation limits – this market wasn't covered at all. By law." Before its spectacular collapse, Enron would use this loophole in 2001 to help engineer an energy crisis in California, artificially constraining the supply of natural gas and power generation, causing price spikes and rolling blackouts. This blatant and criminal market manipulation has become part of the legend of Enron. But Koch was caught up in the debacle. The CFTC would charge that a partnership between Koch and the utility Entergy had, at the height of the California crisis, reported fake natural-gas trades to reporting firms and also "knowingly reported false prices and/or volumes" on real trades. One of 10 companies punished for such schemes, Entergy-Koch avoided prosecution by paying a $3 million fine as part of a 2004 settlement with the CFTC, in which it did not admit guilt to the commission's charges but is barred from maintaining its innocence. Trading, which had long been peripheral to the company's core businesses, soon took center stage. In 2002, the company launched a subsidiary, Koch Supply & Trading. KS&T got off to a rocky start. "A series of bad trades," writes a Koch insider, "boiled over in early 2004 when a large 'sure bet' crude-oil trade went south, resulting in a quick, multimillion loss." But Koch traders quickly adjusted to the reality that energy markets were no longer ruled just by supply and demand – but by rich speculators trying to game the market. Revamping its strategy, Koch Industries soon began bragging of record profits. From 2003 to 2012, KS&T trading volumes exploded – up 450 percent. By 2009, KS&T ranked among the world's top-five oil traders, and by 2011, the company billed itself as "one of the leading quantitative traders" – though Holden now says it's no longer in this business. Trading with IranArtificially constraining oil supplies is not the only source of dark, unregulated profit for Koch Industries. In the years after George W. Bush branded Iran a member of the "Axis of Evil," the Koch brothers profited from trade with the state sponsor of terror and reckless would-be nuclear power. For decades, U.S. companies have been forbidden from doing business with the Ayatollahs, but Koch Industries exploited a loophole in 1996 sanctions that made it possible for foreign subsidiaries of U.S. companies to do some business in Iran. In the ensuing years, according to Bloomberg Markets, the German and Italian arms of Koch-Glitsch, a Koch subsidiary that makes equipment for oil fields and refineries, won lucrative contracts to supply Iran's Zagros plant, the largest methanol plant in the world. And thanks in part to Koch, methanol is now one of Iran's leading non-oil exports. "Every single chance they had to do business with Iran, or anyone else, they did," said Koch whistle-blower George Bentu. Having signed on to work for a company that lists "integrity" as its top value, Bentu added, "You feel totally betrayed. Everything Koch stood for was a lie." Koch reportedly kept trading with Tehran until 2007 – after the regime was exposed for supplying IEDs to Iraqi insurgents killing U.S. troops. According to lawyer Holden, Koch has since "decided that none of its subsidiaries would engage in trade involving Iran, even where such trade is permissible under U.S. law." Tar SandsThese days, Koch's most disquieting foreign dealings are in Canada, where the company has massive investments in dirty tar sands. The company's 1.1 million acres of leases in northern Alberta contain reserves of economically recoverable oil numbering in the billions of barrels. With these massive leaseholdings, Koch is poised to continue profiting from Canadian crude whether or not the Keystone XL pipeline gains approval, says Andrew Leach, an energy and environmental economist at the business school of the University of Alberta. Counter-intuitively, approval of Keystone XL could actually harm one of Koch's most profitable businesses – its Pine Bend refinery in Minnesota. Because tar-sands crude presently has no easy outlet to the global market, there's a glut of Canadian oil in the midcontinent, and Koch's refinery is a beneficiary of this oversupply; the resulting discount can exceed $20 a barrel compared to conventional crude. If it is ever built, the Keystone XL pipeline will provide a link to Gulf Coast refineries – and thus the global export market, which would erase much of that discount and eat into company profit margins. Leach says Koch Industries' tar-sands leaseholdings have them hedged against the potential approval of Keystone XL. The pipeline would increase the value of Canadian tar-sands deposits overnight. Koch could then profit handsomely by flipping its leases to more established producers. "Optimizing asset value through trading," Koch literature says of these and other holdings, is a "key" company strategy. The one truly bad outcome for Koch would be if Keystone XL were to be defeated, as many environmentalists believe it must be. "If the signal that sends is that no new pipelines will be built across the U.S. border for carrying oil-sands product," Leach says, "that's going to have an impact not just on Koch leases, but on everybody's asset value in oil sands." Ironically, what's best for Koch's tar-sands interests is what the Obama administration is currently delivering: "They're actually ahead if Keystone XL gets delayed a while but hangs around as something that still might happen," Leach says.

|

The Koch family, mid-1950s. (Photo: Wichita State University Libraries)The Koch family's lucrative blend of pollution, speculation, law-bending and self-righteousness stretches back to the early 20th century, when Charles' father first entered the oil business. Fred C. Koch was born in 1900 in Quanah, Texas – a sunbaked patch of prairie across the Red River from Oklahoma. Fred was the second son of Hotze "Harry" Koch, a Dutch immigrant who – as recalled in Koch literature – ran "a modest newspaper business" amid the dusty poverty of Quanah. In the family legend, Fred Koch emerged from the nothing of the Texas range to found an empire. But like many stories the company likes to tell about itself, this piece of Kochlore takes liberties with the truth. Fred was not a simple country boy, and his father was not just a small-town publisher. Harry Koch was also a local railroad baron who used his newspaper to promote the Quanah, Acme & Pacific railways. A director and founding shareholder of the company, Harry sought to build a rail line across Texas to El Paso. He hoped to turn Quanah into "the most important railroad center in northwest Texas and a metropolitan city of first rank." He may not have fulfilled those ambitions, but Harry did build up what one friend called "a handsome pile of dinero." Harry was not just the financial springboard for the Koch dynasty, he was also its wellspring of far-right politics. Harry editorialized against fiat money, demanded hangings for "habitual criminals" and blasted Social Security as inviting sloth. At the depths of the Depression, he demanded that elected officials in Washington should stop trying to fix the economy: "Business," he wrote, "has always found a way to overcome various recessions." In the company's telling, young Fred was an innovator whose inventions helped revolutionize the oil industry. But there is much more to this story. In its early days, refining oil was a dirty and wasteful practice. But around 1920, Universal Oil Products introduced a clean and hugely profitable way to "crack" heavy crude, breaking it down under heat and heavy pressure to boost gasoline yields. In 1925, Fred, who earned a degree in chemical engineering from MIT, partnered with a former Universal engineer named Lewis Winkler and designed a near carbon copy of the Universal cracking apparatus – making only tiny, unpatentable tweaks. Relying on family connections, Fred soon landed his first client – an Oklahoma refinery owned by his maternal uncle L.B. Simmons. In a flash, Winkler-Koch Engineering Co. had contracts to install its knockoff cracking equipment all over the heartland, undercutting Universal by charging a one-time fee rather than ongoing royalties. It was a boom business. That is, until Universal sued in 1929, accusing WinklerKoch of stealing its intellectual property. With his domestic business tied up in court, Fred started looking for partners abroad and was soon doing business in the Soviet Union, where leader Joseph Stalin had just launched his first Five Year Plan. Stalin sought to fund his country's industrialization by selling oil into the lucrative European export market. But the Soviet Union's reserves were notoriously hard to refine. The USSR needed cracking technology, and the Oil Directorate of the Supreme Council of the National Economy took a shining to Winkler-Koch – primarily because Koch's oil-industry competitors were reluctant to do business with totalitarian Communists. Between 1929 and 1931, Winkler-Koch built 15 cracking units for the Soviets. Although Stalin's evil was no secret, it wasn't until Fred visited the Soviet Union, that these dealings seemed to affect his conscience. "I went to the USSR in 1930 and found it a land of hunger, misery and terror," he would later write. Even so, he agreed to give the Soviets the engineering know-how they would need to keep building more. Back home, Fred was busy building a life of baronial splendor. He met his wife, Mary, the Wellesley-educated daughter of a Kansas City surgeon, on a polo field and soon bought 160 acres across from the Wichita Country Club, where they built a Tudorstyle mansion. As chronicled in Sons of Wichita, Daniel Schulman's investigation of the Koch dynasty, the compound was quickly bursting with princes: Frederick arrived in 1933, followed by Charles in 1935 and twins David and Bill in 1940. Fred Koch lorded over his domain. "My mother was afraid of my father," said Bill, as were the four boys, especially first-born Frederick, an artistic kid with a talent for the theater. "Father wanted to make all his boys into men, and Freddie couldn't relate to that regime," Charles recalled. Frederick got shipped East to boarding school and was all but disappeared from Wichita. With Frederick gone, Charles forged a deep alliance with David, the more athletic and assertive of the young twins. "I was closer with David because he was better at everything," Charles has said. Fred Koch's legal battle with Universal would drag on for nearly a quarter-century. In 1934, a lower court ruled that Winkler-Koch had infringed on Universal's technology. But that judgment would be vacated, after it came out in 1943 that Universal had bought off one of the judges handling the appeal. A year later, the Supreme Court decided that Fred's cracker, by virtue of small technical differences, did not violate the Universal patent. Fred countersued on antitrust grounds, arguing that Universal had wielded patents anti-competitively. He'd win a $1.5 million settlement in 1952. Around that time, Fred had built a domestic oil empire under a new company eventually called Rock Island Oil & Refining, transporting crude from wellheads to refineries by truck or by pipe. In those later years, Fred also became a major benefactor and board member of the John Birch Society, the rabidly anti-communist organization founded in 1958 by candy magnate and virulent racist Robert Welch. Bircher publications warned that the Red endgame was the creation of the "Negro Soviet Republic" in the Deep South. In his own writing, Fred described integration as a Red plot to "enslave both the white and black man." Like his father, Charles Koch attended MIT. After he graduated in 1959 with two master's degrees in engineering, his father issued an ultimatum: Come back to Wichita or I'll sell the business. "Papa laid it on the line," recalled David. So Charles returned home, immersing himself in his father's world – not simply joining the John Birch Society, but also opening a Bircher bookstore. The Birchers had high hopes for young Charles. As Koch family friend Robert Love wrote in a letter to Welch: "Charles Koch can, if he desires, finance a large operation, however, he must continually be brought along." But Charles was already falling under the sway of a charismatic radio personality named Robert LeFevre, founder of the Freedom School, a whites-only libertarian boot camp in the foothills above Colorado Springs, Colorado. LeFevre preached a form of anarchic capitalism in which the individual should be freed from almost all government power. Charles soon had to make a choice. While the Birchers supported the Vietnam War, his new guru was a pacifist who equated militarism with out-of-control state power. LeFevre's stark influence on Koch's thinking is crystallized in a manifesto Charles wrote for the Libertarian Review in the 1970s, recently unearthed by Schulman, titled "The Business Community: Resisting Regulation." Charles lays out principles that gird today's Tea Party movement. Referring to regulation as "totalitarian," the 41-year-old Charles claimed business leaders had been "hoodwinked" by the notion that regulation is "in the public interest." He advocated the "barest possible obedience" to regulation and implored, "Do not cooperate voluntarily, instead, resist whenever and to whatever extent you legally can in the name of justice." After his father died in 1967, Charles, now in command of the family business, renamed it Koch Industries. It had grown into one of the 10 largest privately owned firms in the country, buying and selling some 80 million barrels of oil a year and operating 3,000 miles of pipeline. A black-diamond skier and white-water kayaker, Charles ran the business with an adrenaline junkie's aggressiveness. The company would build pipelines to promising oil fields without a contract from the producers and park tanker trucks beside wildcatters' wells, waiting for the first drops of crude to flow. "Our willingness to move quickly, absorb more risk," Charles would write, "enabled us to become the leading crude-oilgathering company." Charles also reconnected with one of his father's earliest insights: There's big money in dirty oil. In the late 1950s, Fred Koch had bought a minority stake in a Minnesota refinery that processed heavy Canadian crude. "We could run the lousiest crude in the world," said his business partner J. Howard Marshall II – the future Mr. Anna Nicole Smith. Sensing an opportunity for huge profits, Charles struck a deal to convert Marshall's ownership stake in the refinery into stock in Koch Industries. Suddenly the majority owner, the company soon bought the rest of the refinery outright.

$296 million – then the largest wrongful-death judgment in American legal historyOn the day before Danielle Smalley was to leave for college, she and her friend Jason Stone were hanging out in her family's mobile home. Seventeen years old, with long chestnut hair, Danielle began to feel nauseated. "Dad," she said, "we smell gas." It was 3:45 in the afternoon on August 24th, 1996, near Lively, Texas, some 50 miles southeast of Dallas. The Smalleys were too poor to own a telephone. So the teens jumped into her dad's 1964 Chevy pickup to alert the authorities. As they drove away, the truck stalled where the driveway crossed a dry creek bed. Danielle cranked the ignition, and a fireball engulfed the truck. "You see two children burned to death in front of you – you never forget that," Danielle's father, Danny, would later tell reporters. Unknown to the Smalleys, a decrepit Koch pipeline carrying liquid butane – literally, lighter fluid – ran through their subdivision. It had ruptured, filling the creek bed with vapor, and the spark from the pickup's ignition had set off a bomb. Federal investigators documented both "severe corrosion" and "mechanical damage" in the pipeline. A National Transportation Safety Board report would cite the "failure of Koch Pipeline Company LP to adequately protect its pipeline from corrosion." Installed in the early Eighties, the pipeline had been out of commission for three years. When Koch decided to start it up again in 1995, a water-pressure test had blown the pipe open. An inspection of just a few dozen miles of pipe near the Smalley home found 538 corrosion defects. The industry's term of art for a pipeline in this condition is Swiss cheese, according to the testimony of an expert witness – "essentially the pipeline is gone." Koch repaired only 80 of the defects – enough to allow the pipeline to withstand another pressure check – and began running explosive fluid down the line at high pressure in January 1996. A month later, employees discovered that a key anticorrosion system had malfunctioned, but it was never fixed. Charles Koch had made it clear to managers that they were expected to slash costs and boost profits. In a sternly worded memo that April, Charles had ordered his top managers to cut expenditures by 10 percent "through the elimination of waste (I'm sure there is much more waste than that)" in order to increase pre-tax earnings by $550 million a year. The Smalley trial underscored something Bill Koch had said about the way his brothers ran the company: "Koch Industries has a philosophy that profits are above everything else." A former Koch manager, Kenoth Whitstine, testified to incidents in which Koch Industries placed profits over public safety. As one supervisor had told him, regulatory fines "usually didn't amount to much" and, besides, the company had "a stable full of lawyers in Wichita that handled those situations." When Whitstine told another manager he was concerned that unsafe pipelines could cause a deadly accident, this manager said that it was more profitable for the company to risk litigation than to repair faulty equipment. The company could "pay off a lawsuit from an incident and still be money ahead," he said, describing the principles of MBM to a T. At trial, Danny Smalley asked for a judgment large enough to make the billionaires feel pain: "Let Koch take their child out there and put their children on the pipeline, open it up and let one of them die," he told the jury. "And then tell me what that's worth." The jury was emphatic, awarding Smalley $296 million – then the largest wrongful-death judgment in American legal history. He later settled with Koch for an undisclosed sum and now runs a pipeline-safety foundation in his daughter's name. He declined to comment for this story. "It upsets him too much," says an associate. Recklessness be goneThe official Koch line is that scandals that caused the company millions in fines, judgments and penalties prompted a change in Charles' attitude of regulatory resistance. In his 2007 book, The Science of Success, he begrudgingly acknowledges his company's recklessness. "While business was becoming increasingly regulated," he reflects, "we kept thinking and acting as if we lived in a pure market economy. The reality was far different." Charles has since committed Koch Industries to obeying federal regulations. "Even when faced with laws we think are counterproductive," he writes, "we must first comply." Underscoring just how out of bounds Koch had ventured in its corporate culture, Charles admits that "it required a monumental undertaking to integrate compliance into every aspect of the company." In 2000, Koch Petroleum Group entered into an agreement with the EPA and the Justice Department to spend $80 million at three refineries to bring them into compliance with the Clean Air Act. After hitting Koch with a $4.5 million penalty, the EPA granted the company a "clean slate" for certain past violations. Then George W. Bush entered the White House in 2001, his campaign fattened with Koch money. Charles Koch may decry cronyism as "nothing more than welfare for the rich and powerful," but he put his company to work, hand in glove, with the Bush White House. Correspondence, contacts and visits among Koch Industries representatives and the Bush White House generated nearly 20,000 pages of records, according to a Rolling Stone FOIA request of the George W. Bush Presidential Library. In 2007, the administration installed a fiercely anti-regulatory academic, Susan Dudley, who hailed from the Koch-funded Mercatus Center at George Mason University, as its top regulatory official. Today, Koch points to awards it has won for safety and environmental excellence. "Koch companies have a strong record of compliance," Holden, Koch's top lawyer, tells Rolling Stone. "In the distant past, when we failed to meet these standards, we took steps to ensure that we were building a culture of 10,000 percent compliance, with 100 percent of our employees complying 100 percent." To reduce its liability, Koch has also unwound its pipeline business, from 37,000 miles in the late 1990s to about 4,000 miles. Of the much smaller operation, he adds, "Koch's pipeline practice and operations today are the best in the industry." KOCH CompaniesSince Koch Industries aggressively expanded into high finance, the net worth of each brother has also exploded – from roughly $4 billion in 2002 to more than $40 billion today. In that period, the company embarked on a corporate buying spree that has taken it well beyond petroleum. In 2005, Koch purchased Georgia Pacific for $21 billion, giving the company a familiar, expansive grip on the industrial web that transforms Southern pine into consumer goods – from plywood sold at Home Depot to brand-name products like Dixie Cups and Angel Soft toilet paper. In 2013, Koch leapt into high technology with the $7 billion acquisition of Molex, a manufacturer of more than 100,000 electronics components and a top supplier to smartphone makers, including Apple. Koch Supply & Trading makes money both from physical trades that move oil and commodities across oceans as well as in "paper" trades involving nothing more than high-stakes bets and cash. In paper trading, Koch's products extend far beyond simple oil futures. Koch pioneered, for sale to hedge funds, "volatility swaps," in which the actual price of crude is irrelevant and what matters is only the "magnitude of daily fluctuations in prices." Steve Mawer, until recently the president of KS&T, described parts of his trading operation as "black-box stuff." Like a casino that bets at its own craps table, Koch engages in "proprietary trading" – speculating for the company's own bottom line. "We're like a hedge fund and a dealer at the same time," bragged Ilia Bouchouev, head of Koch's derivatives trading in 2004. "We can both make markets and speculate." The company's many tentacles in the physical oil business give Koch rich insight into market conditions and disruptions that can inform its speculative bets. When oil prices spiked to record heights in 2008, Koch was a major player in the speculative markets, according to documents leaked by Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, with trading volumes rivaling Wall Street giants like Citibank. Koch rode a trader-driven frenzy – detached from actual supply and demand – that drove prices above $147 a barrel in July 2008, battering a global economy about to enter a free fall. Only Koch knows how much money Koch reaped during this price spike. But, as a proxy, consider the $20 million Koch and its subsidiaries spent lobbying Congress in 2008 – before then, its biggest annual lobbying expense had been $5 million – seeking to derail a raft of consumer-protection bills, including:

In comments to the Federal Trade Commission, Koch lobbyists defended the company's right to rack up fantastic profits at the expense of American consumers. "A mere attempt to maximize profits cannot constitute market manipulation," they wrote, adding baldly, "Excessive profits in the face of shortages are desirable." When the global economy crashed in 2008, so did oil prices. By December, crude was trading more than $100 lower per barrel than it had just months earlier – around $30. At the same time, oil traders anticipated that prices would eventually rebound. Futures contracts for delivery of oil in December 2009 were trading at nearly $55 per barrel. When future delivery is more valuable than present inventory, the market is said to be "in contango." Koch exploited the contango market to the hilt. The company leased nine supertankers and filled them with cut-rate crude and parked them quietly offshore in the Gulf of Mexico, banking virtually risk-free profits by selling contracts for future delivery. All in, Koch took about 20 million barrels of oil off the market, putting itself in a position to bet on price disruptions the company itself was creating. Thanks to these kinds of trading efforts, Koch could boast in a 2009 review that "the performance of Koch Supply & Trading actually grew stronger last year as the global economy worsened." The cost for those risk-free profits was paid by consumers at the pump. Estimates pegged the cost of the contango trade by Koch and others at up to 40 cents a gallon.

|

The Dodd-Frank bill was supposed to put an end to economyendangering speculation in the $700 trillion global derivatives market. But Koch has managed to defend – and even expand – its turf, trading in largely unregulated derivatives, once dubbed "financial weapons of mass destruction" by billionaire Warren Buffett.

In theory, the Enron Loophole is no longer open – the government now has the power to police manipulation in the market for energy derivatives. But the Obama administration has not yet been able to come up with new rules that actually do so. In 2011, the CFTC mandated "position limits" on derivative trades of oil and other commodities. These would have blocked any single speculator from owning futures contracts representing more than a quarter of the physical market – reducing the danger of manipulation. As part of the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, which also reps many Wall Street giants including Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan Chase, Koch fought these new restrictions. ISDA sued to block the position limits – and won in court in September 2012. Two years later, CFTC is still spinning its wheels on a replacement. Industry traders like Koch are, Greenberger says, "essentially able to operate as though the Enron Loophole were still in effect."

Koch is also reaping the benefits from Dodd-Frank's impacts on Wall Street. The so-called Volcker Rule, implemented at the end of last year, bans investment banks from "proprietary trading" – investing on their own behalf in securities and derivatives. As a result, many Wall Street banks are unloading their commodities-trading units. But Volcker does not apply to nonbank traders like Koch. They're now able to pick up clients who might previously have traded with JPMorgan. In its marketing materials for its trading operations, Koch boasts to potential clients that it can provide "physical and financial market liquidity at times when others pull back." Koch also likely benefits from loopholes that exempt the company from posting collateral for derivatives trades and allow it to continue trading swaps without posting the transactions to a transparent electronic exchange. Though competitors like BP and Cargill have registered with the CFTC as swaps dealers – subjecting their trades to tightened regulation – Koch conspicuously has not. "Koch is compliant with all CFTC regulations, including those relating to swaps dealers," says Holden, the Koch lawyer.

That a massive company with such a troubling record as Koch Industries remains unfettered by financial regulation should strike fear in the heart of anyone with a stake in the health of the American economy. Though Koch has cultivated a reputation as an economically conservative company, it has long flirted with danger. And that it has not suffered a catastrophic loss in the past 15 years would seem to be as much about luck as about skillful management.

The Kochs have brushed up against some of the major debacles of the crisis years. In 2007, as the economy began to teeter, Koch was gearing up to plunge into the market for credit default swaps, even creating an affiliate, Koch Financial Products, for that express purpose. KFP secured a AAA rating from Moody's and reportedly sought to buy up toxic assets at the center of the financial crisis at up to 50-times leverage. Ultimately, Koch Industries survived the experiment without losing its shirt.

More recently, Koch was exposed to the fiasco at MF Global, the disgraced brokerage firm run by former New Jersey Gov. Jon Corzine that improperly dipped into customer accounts to finance reckless bets on European debt. Koch, one of MF Global's top clients, reportedly told trading partners it was switching accounts about a month before the brokerage declared bankruptcy – then the eighth-largest in U.S. history. Koch says the decision to pull its funds from MF Global was made more than a year before. While MF's small-fry clients had to pick at the carcass of Corzine's company to recoup their assets, Koch was already swimming free and clear.

Because it's private, no one outside of Koch

Industries knows how much risk Koch is taking – or

whether it could conceivably create systemic risk, a concern raised in 2013 by

the head of the Futures Industry Association. But

this much is for certain: Because of the loopholes in

financial-regulatory reform, the next company to put the American economy

at risk may not be a Wall Street bank but a trading giant like Koch. In 2012,

Gary Gensler, then CFTC chair, railed against the

very loopholes Koch appears to be exploiting,

raising the specter of AIG.

"[AIG] had this massive risk built up in its

derivatives just because it called itself an insurance company rather than a

bank," Gensler said. When Congress adopted Dodd-Frank,

Gensler added, it never intended to exempt financial heavy hitters just because

"somebody calls themselves an insurance company"

In "the science of success," Charles Koch highlights the problems created when property owners "don't benefit from all the value they create and don't bear the full cost from whatever value they destroy." He is particularly concerned about the "tragedy of the commons," in which shared resources are abused because there's no individual accountability. "The biggest problems in society," he writes, "have occurred in those areas thought to be best controlled in common: the atmosphere, bodies of water, air. . . ."

But in the real world, Koch Industries has used its political might to beat back the very market-based mechanisms that (– including a cap-and-trade market for carbon pollution – needed to create the ownership rights for pollution that Charles says) would improve the functioning of capitalism.

| In fact, it appears the very essence of

the Koch business model is to exploit breakdowns in

the free market. Koch has profited precisely by

dumping billions of pounds of pollutants into our

waters and skies – essentially for free. It racks up enormous profits from

speculative trades lacking economic value that drive up costs for consumers

and create risks for our economy. The Koch brothers get richer as the costs of what Koch destroys are foisted on the rest of us – in the form of ill health, foul water and a climate crisis that threatens life as we know it on this planet. Now nearing 80 – owning a large chunk of the Alberta tar sands and using his billions to transform the modern Republican Party into a protection racket for Koch Industries' profits – Charles Koch is not about to see the light. Nor does the CEO of one of America's most toxic firms have any notion of slowing down. He has made it clear that he has no retirement plans: "I'm going to ride my bicycle till I fall off." |

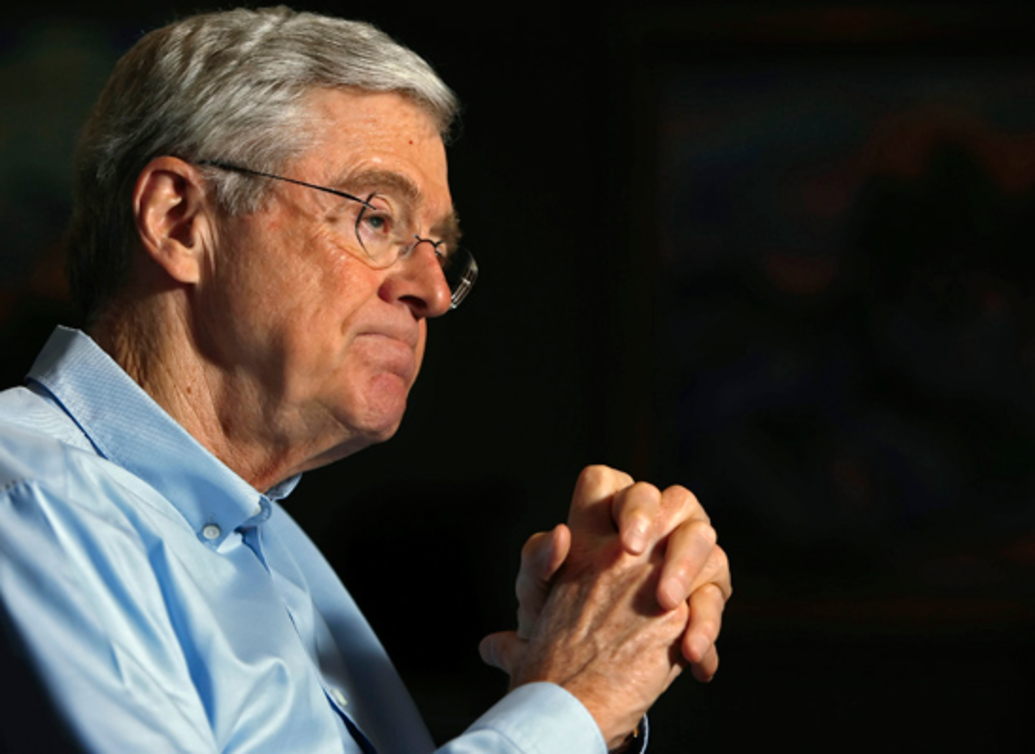

Charles Koch (Photo: Larry W. Smith / Polaris) |

|

UPDATE: Koch Industries Responds to Rolling Stone — And We Answer Back Read more: http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/inside-the-koch-brothers-toxic-empire-20140924#ixzz3Evy5S6HB

|